During the last couple of years I’ve written several articles about the Sockum family, notable for their unique surname and probable connection to the Nanticoke Indians. It’s a bit easier to research an unusual name like Sockum than others that are associated with the Nanticokes and Moors, such as Clark and Johnson.

The name Ridgeway might seem, at first glance, to be similarly mainstream, but a closer look at the Ridgeway family reveals that their name wasn’t originally Ridgeway, and they can be traced to a specific neighborhood in Sussex County. Considering their association with one of the oldest legends about the Moors’ origins, they are certainly deserving of more attention than they’ve received.

Notable Ridgeways include Eunice Ridgeway (1813 – 1896), the wife of Levin Sockum; and Cornelius Ridgeway, who was described as the “patriarch” of the Cheswold Moors in 1895, and who related a version of the legend in question.

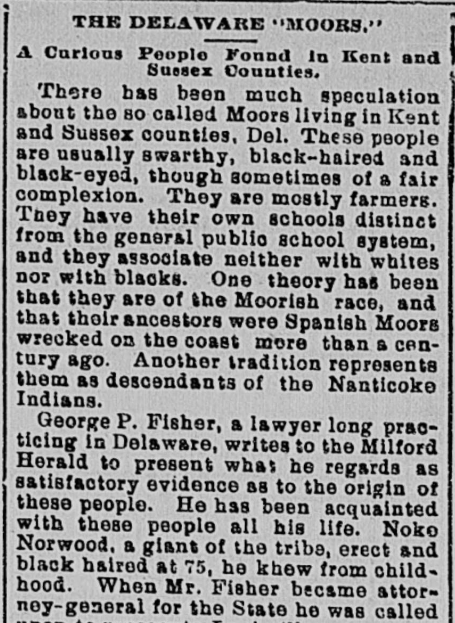

Though there are a number of versions of what C. A. Weslager later dubbed the Romantic Legend, dating back to the 1850s but primarily recorded in the 1890s, many of the details are consistent. Rather than quote or summarize each version individually, I’ll list the core points:

- A white woman settled in or near Angola Neck, southwest of Lewes and in Indian River Hundred, roughly fifteen to twenty years before the American Revolution (i.e., 1756 – 1761).

- She was either Irish or Spanish, or, in one version, Irish with a claim to an estate in Spain.

- Her name was Regua, Señorita Requa, or Miss Reegan.

- She purchased some newly arrived slaves in Lewes, one of whom was very handsome. According to most versions, he could speak Spanish, and told her he was a Spanish and/or Moorish prince who had been sold into slavery. In one version, his name was Requa.

- The two married and produced mixed descendants who were scorned by the local whites, yet did not wish to marry the local blacks, so they either intermarried amongst themselves or married Indians. Their descendants in Indian River Hundred were numerous. Red hair is often mentioned.

- The name Regua (or Requa, etc.) evolved into the surname Ridgeway.

The facts are less dramatic, though they don’t disprove any of the plot points listed above, and are remarkably compatible with them.

John Regua, Indian River Hundred, 1740s – 1790s?

A mulatto whose name was recorded as John Rigway, John Regua, John Rigwaugh, John Rigwaw, and John Rigware, among other similar spellings, was living in Indian River Hundred as early as the 1740s. His daughters were baptized at St. George’s in 1748, and he purchased nearly 300 acres of land near Swan Creek from Cord Hazzard between 1753 and 1754. Variations of his name appear on tax lists throughout the following decades, and in my opinion, most of these creative spellings suggest that the name was not pronounced like the English surname Ridgeway. It seems more likely that the writers were struggling to spell a name which was unfamiliar, and probably foreign.

Although Regua is a rather obscure term, it could very well be Portuguese. Peso de Régua (or Pezo de Regoa) is a city in northern Portugal, and similar names can be found in Spain and in the Pacific. It should perhaps be noted here that another surname suspected to be of Portuguese or Spanish origin, Driggas or Driggers (possibly derived from Rodrigues or Rodriguez), appears in Indian River Hundred as early as 1770.

Little is known of John’s immediate family, and it’s difficult to connect the dots between him and later generations with certainty, but it’s likely that he had sons named William and Isaac, who, like him, appear in early tax lists for Indian River Hundred, as well as the records of St. George’s. In July 1785, William and Jane Riguway baptized a child who had been born nearly a year earlier, and just a few weeks later, Isaac and Lydia Riguway baptized a daughter named Allender. Isaac’s fate is unknown, but William appears in a number of records including the 1820 census (which vaguely described him as being 45 or older), and died before November 1826.

The Rigware family in Indian River Hundred, 1810 – 1840s

Census records allow us to identify several Rigware households in Indian River Hundred between 1810 and 1840, headed by:

- William Rigware, Sr., enumerated in 1820 and most likely the same man who was a taxable as early as 1774, and who is assumed to be John Regua’s eldest son. Interestingly, William’s household included one female slave who was 45 or older in 1820.

- Peter Rigware, age unknown, enumerated in 1810.

- John Rigware, enumerated in 1810 and 1820 with a birthdate range of 1776 – 1794. He is most likely the same man who appears in the 1830 census as John Rigway, aged 55-99, with a birthdate range of 1731 – 1775, and again in the 1850 census as 73-year-old John Ridgeway, living in the household of Nathaniel Clark in Lewis and Rehoboth Hundred. Comparison of these slightly conflicting records suggests that he was born circa 1776.

- Simon Rigware, enumerated in 1820 and 1840, with a birthdate range of 1776 – 1785. In 1840, his name was given as “Simon Rigware alias Jack.”

- Jacob Rigware, enumerated in 1820 with a birthdate range of 1776 – 1794. In 1850, a 60-year-old Jacob Ridgway was living in the household of John and Hetty Harmon in Broadkill Hundred. If they are the same man, then Jacob was born circa 1790.

With the exception of the enigmatic female slave living in William Rigware’s household in 1820 (who may very well have been a family member), all of these men and their family members were described as free colored persons or mulattoes. Although researchers using resources like Ancestry.com will find transcribed spellings like Rigwars and Rigwan, a closer look at the handwritten records suggested that the correct spelling is, indeed, Rigware. It should be noted that during this period, the family remained concentrated in Indian River Hundred.

Rigware, Ridgway, and Ridgeway in 1850

The 1850 U.S. Federal Census is notable for the amount of information it provides. Previously, only heads of household were named, and the members of the household were vaguely listed by gender and age ranges. In 1850 (and in every census since), each member of the household was identified by name and age. When it comes to the Rigware family, the 1850 census provides evidence for two important trends. First, they had begun to migrate northward, appearing in Lewis and Rehoboth Hundred, Broadkill Hundred, and Cedar Creek Hundred. Second, the name had been changed to Ridgway in certain instances.

Confusingly, the 1850 census also includes a number of Ridgeways who might or might not be related to the Rigwares. Connections to both New Jersey and Indiana are noted, which ought to interest anyone researching Nanticoke genealogy. However, I’ll ignore these households for the moment and focus on those which can reasonably be assumed to be related to the Rigwares of Indian River Hundred.

As was mentioned previously, John Ridgway, a 73-year-old mulatto, was living in the household of Nathaniel Clark in Lewis and Rehoboth Hundred. The name Clark, of course, has been associated with the Nanticoke Indian Association since its beginnings, and it was Lydia Clark who first recited a version of the Romantic Legend in 1855. Nathaniel’s wife was named Unicey, and they also had a daughter named Unicey, which might suggest some connection to Eunice Ridgeway, who was living with her husband, Levin Sockum, in Indian River Hundred at the time. It’s possible that the elder Unicey was John’s daughter, in which case her maiden name would have been Rigware or Ridgway. Some relationship between all of these individuals seems likely.

Another John Ridgway was living in Broadkill Hundred at the time, though this one was 35. His wife, Sophia, was 20, while a third member of the household, 18-year-old Matilda Ridgway, may have been a younger sister.

Also in Broadkill Hundred was the household of John Harmon, who was 25. The only other members were his wife, Hetty, who was 20, and Jacob Ridgway, 60.

Moving northward, we come to the household of William Rigware, age 46, in Cedar Creek Hundred. He is assumed to have been the son of William Rigware, Sr., who lived in Indian River Hundred. William is notable for three reasons:

- He was the father of Cornelius Ridgeway, who was later described as the patriarch of the Cheswold Moors, and who remembered a version of the Romantic Legend.

- He continued to migrate northward between 1850 and 1860; when one considers his assumed residence in Indian River Hundred between his birth around 1804 and his father’s death in 1826, he is practically a direct link between the Indian River and Cheswold communities.

- By 1860, he, too, had changed his surname to Ridgeway.

Another person of interest in the 1850 census is a mulatto named Tilman (or Tilghman) Jack, who was living in Dover Hundred with his wife and six children. By 1870, he had become Tilghman Ridway and was living in Northwest Fork Hundred, near Seaford; by 1880, Tilghman Ridgeway and family were back in Dover. It should be remembered that Simon Rigware of Indian River Hundred was called “Simon Rigware alias Jack” in 1840. The significance of the Jack name is unclear.

The Ridgeway family in Kent County, 1850s – 1890s

By 1860, William Rigware had become William Ridgeway, and had moved his family to Duck Creek Hundred. Personally, I believe the change from Rigware to Ridgeway was deliberate. The former spelling, which followed older spellings like Rigwaugh and Regua, was used consistently for decades. I find it hard to believe that multiple individuals previously known as Rigwares suddenly became Ridgways or Ridgeways in 1850 without having decided to. It was not long after this that Levin Sockum’s family changed both the spelling and pronunciation of their surname to Sockume (sock-yoom). It’s possible that some of the multiracial families who claimed Indian ancestry changed their names during this period in a subtle attempt to improve their social status. Rigware was a mulatto name, Ridgeway was a white name — or so they may have reasoned. This is not to say that they were attempting to claim to be white; they continued to be described as mulattoes, and sometimes as blacks. Yet Weslager wrote of some of the Cheswold Moors successfully “passing” for white and moving away.

Cornelius Ridgeway — who was probably the great-grandson of John Regua — was talking about his own family’s history when he told a journalist about the legend of Señorita Requa in 1895, and had himself been a Rigware as a young boy.

Conclusion

Although there is no evidence that the Ridgeway family associated with the Nanticokes and Moors is descended from a white woman who married a handsome slave on her plantation in the Angola area in the 1750s, it’s a matter of fact that a free mulatto named John Regua bought a considerable amount of land in the right area during the right time period, and his descendants lived in Indian River Hundred for nearly a century before they began to migrate northward, and his surname evolved into Rigware by the late 18th century and Ridgeway by the mid-19th century. These facts are delightfully compatible with the core points of the Romantic Legend.

I should note at this point that there is no obvious connection to the historical Nanticoke Indians who lived along the Nanticoke River. I’ve called Ridgeway a Nanticoke surname in the sense that it is associated with the modern Nanticoke Indian Association and related groups in Kent County and New Jersey.

This article might have raised more questions than it has answered. Who was John Regua? Where did he come from? Where did he come by what seems to be a Portuguese name? Is it a coincidence that men named Driggas were among his neighbors, and Angola Neck was named after a major Portuguese colony?

Other surnames with a possible Portuguese or Spanish connection are found throughout the colonial records of the peninsula, such as Gonsolvos (Gonçalves), Francisco, and Dias. Some of them were associated with the Cheswold Moors.

When one considers these curious facts, the legends of the Nanticokes and Moors — including not only the Romantic Legend, but also tales involving shipwrecked pirates — begin to sound surprisingly plausible.

– Chris Slavens