I was a teenager when I first heard someone use the term Moor to refer to a member of central Sussex County’s multiracial community, which claims and celebrates Native American ancestry. “Moor?” I asked, confused, thinking of northern Africa. “What’s that mean?” The response was quipped like a punchline: “More nigger than anything.”

I didn’t know it at the time, but C. A. Weslager had mentioned a similar tongue-in-cheek explanation of the odd label in his book Delaware’s Forgotten Folk: The Story of the Moors and Nanticokes, published in 1943. During that era of segregation, such a remark was not only a crude joke, but relegated the target to the second-class colored community. Since before the Civil War, Delawareans who claimed Indian ancestry had been accused, by both whites and blacks, of being nothing more than blacks seeking special treatment.

But the local term Moor, as an ethnic label, doesn’t seem to have originated as a racial slur. In fact, the so-called Delaware Moors identified themselves as Moors as early as the 19th century, if not earlier. But what’s the story behind the name?

Scharf’s History of Delaware, published in 1888, offers the following description of the group in question in Sussex County:

In the hundreds of Indian River, Lewes and Rehoboth and Dagsborough are a numerous class of colored people, commonly called yellow men, and by many believed to be descendants of the Indians, which formerly inhabited this country. Others regard them as mulattoes and still others claim that they are of Moorish descent. From the fact that so many of them bear the name of Sockum, that term has also been applied to the entire class of people. Of their genealogy, Judge George P. Fisher said:

“About one hundred and fifty years ago a cargo of slaves from Congo River was landed at Lewes, and sold to purchasers at that place. Among them was a tall, fine-looking young man about five and twenty years. This man was called Requa, and was remarkable for his manly proportions and regular features, being more Caucasian than African. Requa was purchased by a young Irish widow, having red hair, blue eyes and fair complexion. She afterwards married him. At that time the Nanticoke Indians were still quite numerous at and near Indian River. The offspring of Requa and his Irish wife were not recognized in the white society, and they would not associate with the negroes, and they did associate and intermarry with the Indians.

“This statement was made on oath of Lydia Clark, at Georgetown, in 1856, in the trial of the case of the State against Levin Sockum for selling, contrary to law, powder and shot to one Isaiah Harman, alleged to be a free mulatto. The question upon which the case turned was whether Harman really was a free mulatto, and the genealogy of that race of people was traced by Lydia Clark, then about eighty-seven years of age, who was of the same race of people.

“The court was so well convinced of the truth of Lydia’s testimony that Sockum was convicted of the charge preferred against him.

“This race of people are noted as peaceable, law-abiding citizens, good farmers, and are known as Moors, but without any foundation. The name Requa or Regua is now handed down as Ridgeway.”

The exclusiveness spoken of continues to the present time. This class of people maintains its separate social life (so far as it is possible to do so) seldom intermarrying with the negroes or mulattoes, and support separate churches. The number in the county is diminishing, owning to removals and natural causes but enough remain to make it a distinctive element.

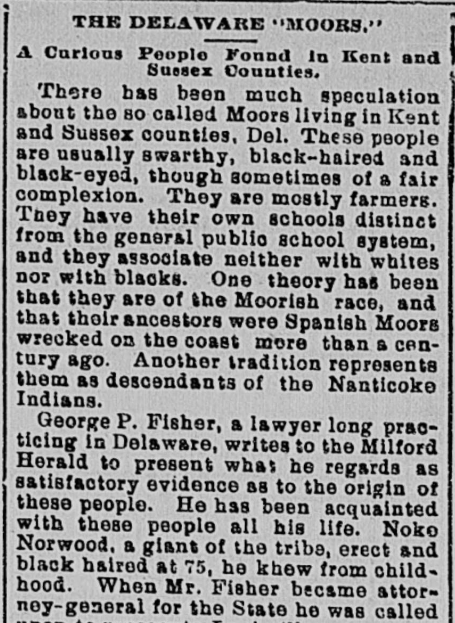

Interestingly, Fisher wrote an article for the Milford Herald in 1895 which offers a somewhat different version of the story (which was picked up by numerous newspapers across the country around that time). In this slightly later version, it is the Irish lady who was named Regua, and she purchased a slave of “dark ginger-bread color, who claimed to be a prince or chief of one of the tribes of the Congo River…” Though most of the details are the same, the few differences raise questions about Fisher’s reliability, as in each case he is supposedly recounting Lydia Clark’s testimony.

The article from 1895 might be more valuable for Fisher’s recollections from his own childhood, particularly of Noke Norwood, said to be Lydia Clark’s brother:

When I was a boy and young man, the general impression prevailing in the several parts of this State where this race of people had settled was that they had sprung from some Spanish Moors who, by chance, had drifted from the southern coast of Spain prior to the Revolutionary War and settled at various points on the Atlantic Coast of the British colonies; but exactly where and when, nobody could tell.

This story of their genesis seemed to have originated with, or at any rate, was adopted by the last Chief Justice, Thomas Clayton, whose great learning and research gave semblance of authority to it, and, like almost everybody else, I accepted it as the true one for many years, although my father, who was born and reared in that portion of Sussex County where these people were more numerous than in any other part of the State, always insisted that they were an admixture of Indian, negro and white man, and gave his reason therefore–that he had always so understood from Noke Norwood, whom I knew when I was a small boy. Noke lived, away back in the 20’s, in a small shanty long since removed, situated near what has been known for more than a century as Sand Tavern Lane, on the West side of the Public Road and nearly in front of the farmhouse now owned by Hon. Jonathan S. Willis, our able and popular Representative in Congress.

I well remember with what awe I contemplated his gigantic form when I first beheld him. My father had known him as a boy, and I never passed his cabin without stopping. He was a dark, copper-colored man, about six feet and half in height, of splendid proportions, perfectly straight, coal black hair (though at least 75 years old), black eyes and high cheek bones.

Fisher was born in 1817, so according to him, a legend concerning Spanish Moors settling on the coast prior to the Revolution was widely known in Delaware during his youth — say, 1820s – 1840. This is important, because Clark never actually said the word Moor in her testimony, and it’s difficult to determine when Delawareans started using the word as an ethnic label.

In 1898, William H. Babcock visited the Indian River community and wrote an article entitled “The Nanticoke Indians of Indian River, Delaware,” which was published in American Anthropologist the following year.

There are two remnants of Indian population in eastern Delaware, not far from the coast — the so-called Moors of Kent county and the more southerly Nanticokes on Indian river in Sussex county.

Of the former I can speak by report only, not having visited them. According to an old legend they are the offspring of Moors shipwrecked near Lewes; a more romantic version gives them only one Moorish progenitor — a captive prince who escaped from his floating prison and found wife and home among the half-Indian population alongshore. There are said to be two or three hundred of these people, clustering mainly around Chesholm, a hamlet and railroad station a few miles south of Dover. The Philadelphia Press for December 1st, 1895, presents a series of portraits which, if accurate, go far to sustain the contention of the Nanticokes that there is not much in common between the two peoples; but their intercourse is too slight and infrequent for their judgment to be conclusive. They consider the Chesholm people to be a mixture of Delaware Indians with some Moorish or other foreign strain. According to their tradition the Nanticoke and Delaware tribes were often at war in the old time, and even yet there would seem to be a barrier of rather more than indifference between them.

Babcock’s distinction between Moors in Kent County and Nanticokes in Sussex County is interesting, though not strictly accurate. Barrier or not, the communities at Cheswold and Indian River were connected by marriage, and shared many of the same surnames (not to mention the same folklore), before 1898 (and probably before the Civil War). Weslager’s later research among the Cheswold Moors revealed that some claimed Nanticoke, and even Pocomoke, ancestry, remembering the specific creeks in Sussex County and Maryland that their grandparents had lived by. And, of course, the members of the Indian River community were known as Moors, too. However, it’s a matter of fact that the Indian River people legally established a new Indian tribe in the form of the Nanticoke Indian Association, while the people at Cheswold continued to call themselves Moors long afterward (though today there is a “Lenape Indian Tribe of Delaware” based in Cheswold). Is this important? Maybe, maybe not.

In his History of the State of Delaware, published in 1908, Henry Clay Conrad made a rather sensational statement in a section about Kent County:

James Green another large owner of land in Duck Creek Hundred owned a large tract in Kenton known as “Brenford,” Philip Lewis took up several large tracts adjoining these and extending from a small settlement known as the “Seven Hickories,” on the road from Dover to where the village of Kenton was eventually built on his land; and one thousand acres adjoining the settlement of “Seven Hickories” were owned by Moors who came to the Hundred direct from Spain in 1710, and who settled in a village known as Moortown on the Dover-Kenton road.

In 1785 these Moors owned large estates and had a prosperous and thriving community. John and Israel Durham were leading members of this settlement. They and their descendants refused to mingle with their white or black neighbors and have maintained to this day their pure Moorish blood. Several families now remain in this section as direct descendants of these Moors.

Conrad’s account seems to be an exaggerated interpretation of a much more reasonable passage in Scharf’s history of Kenton Hundred:

West of the town of Moorton are a class of people who claim that they are original Moors. At one time they owned over a thousand acres between Seven Hickories and Moorton. They claim to have settled here about 1710. In 1785 there were several families owning quite large estates, among whom were John and Israel Durham. They have always lived apart from both white and colored neighbors, and have generally intermarried, and steadily refused to attend the neighboring colored schools. In 1877, Hon. Charles Brown, of Dover, gave them ground and wood for a building near Moore’s Corner, and since that time they have maintained a school there at their own expense. There are about fifteen families remaining.

The information published by Scharf is surprisingly specific. I.e., in the 1880s, the residents of the community west of Moorton claimed Moorish ancestry, and furthermore claimed that their ancestors had settled in the neighborhood circa 1710. These claims are fairly subdued compared to the other legends involving shipwrecks and African princes. This doesn’t make them true, but it does make them difficult to ignore; the researcher feels compelled to take a closer look.

To be continued…

– Chris Slavens